Happy Independence Day!

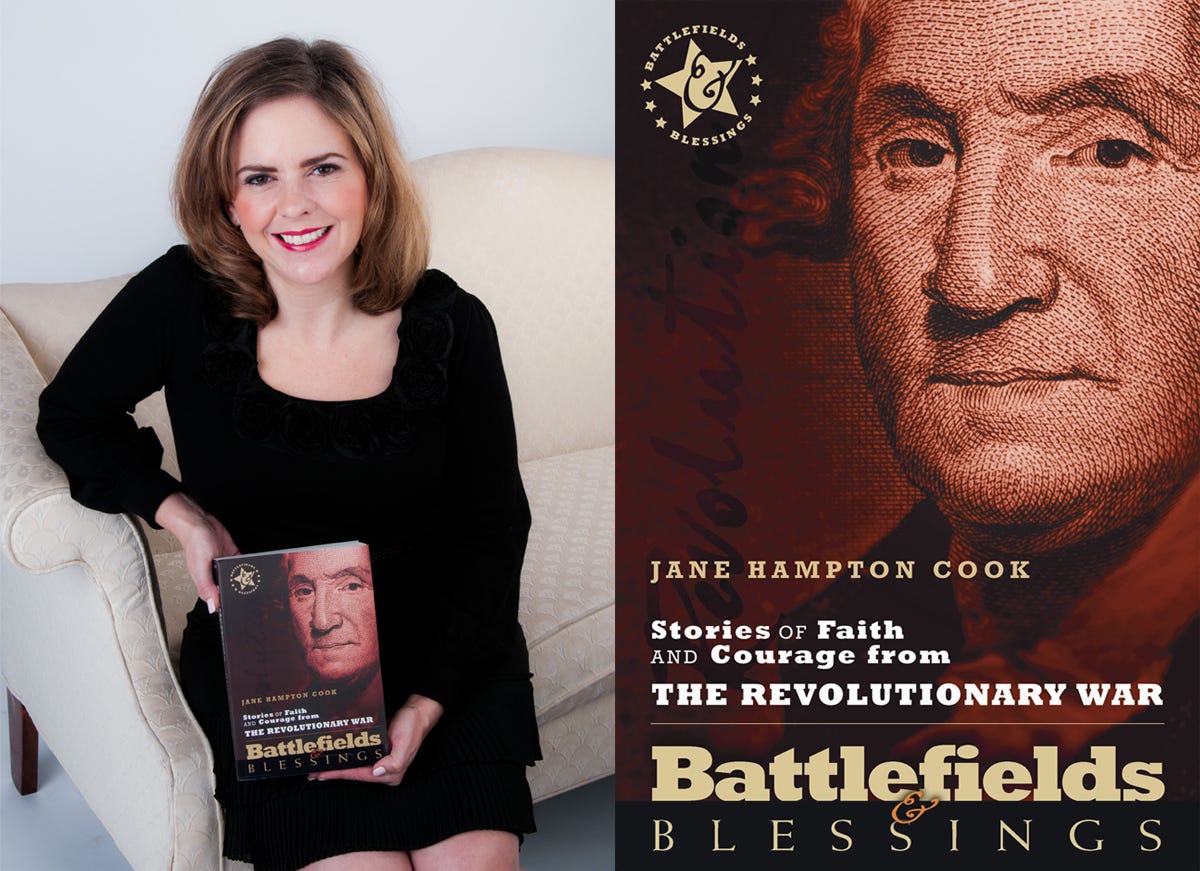

Below are excerpts about the Declaration of Independence from my devotional book, Stories of Faith and Courage from the Revolutionary War.

Jefferson’s Got Talent

Jefferson’s Got Talent

He was the new guy in town. No one who met him failed to notice his youth. When this tall, slender, thirty-three-year-old redhead joined the Continental Congress in Philadelphia in June 1776, he brought with him a freshness to the proceedings.

Jefferson also presented “a reputation for literature, science, and a happy talent for composition,” as John Adams later reflected.

Jefferson arrived at the most pivotal point in Congress’s deliberations. Thomas Paine’s Common Sense had moved many colonists to action. Thousands were ready to crush the English constitution with the club of independence.

“The delegates from Virginia moved in obedience to instructions from their constituents that the Congress should declare that these United colonies . . . be free & independent states,” Jefferson recorded of the actions of Virginia’s elder statesman, Richard Henry Lee.

Lee submitted three resolutions, including one for independence in June 1776. Congress responded by appointing three committees: One to draft a declaration of independence, one to draft a treaty with France, and one to draft a new constitution.

Without experience in diplomacy, Jefferson joined the declaration committee, along with John Adams and Benjamin Franklin.

“The committee for drawing the declaration of Independence desired me to do it,” Jefferson reflected on his assignment to draft the document.

John Adams later explained how the youngest member of the committee came to craft the declaration.

“YOU inquire why so young a man as Mr. Jefferson was placed at the head of the Committee for preparing a Declaration of Independence? I answer: It was the Frankfort advice [referring to an earlier meeting of some colonial leaders in Frankfort, New York], to place Virginia at the head of everything.”

Jefferson was chosen partially because he was from Virginia. Just as Adams had nominated a Virginian, George Washington, for the post of commander-in-chief, in 1775 so he also named Jefferson to write the declaration. He believed the stronger the bonds were between New England and the South, the more likely independence would succeed.

One question remained. Why didn’t forty-six-year-old Richard Henry Lee write the declaration? After all, his resolution first led Congress to consider independence. Adams explained that Lee served on the committee to draft the more lengthy constitution. He didn’t have time to write the shorter declaration.

Although he was the newest delegate, Jefferson impressed his colleagues, especially Adams, with his pen.

“Writings of his [Jefferson’s] were handed about, remarkable for the peculiar felicity of expression,” Adams later recounted. “Though a silent member in Congress, he was so prompt, frank, explicit, and decisive upon committees and in conversation . . . that he soon seized upon my heart.”

And that is how the newbie in Congress came to write one of the most significant political documents ever drafted. Thomas Jefferson wrote it simply because he was chosen. He put on paper the changes in sentiment stirring in the hearts of his countrymen and countrywomen.

Breathless Debate

After emptying what seemed like a thousand bottles of ink, Thomas Jefferson completed the Declaration of Independence in late June 1776. For two weeks, consumed with the concept of independence, he had scratched and smoothed words into a flowing form. But the clock was ticking. It was time for Congress to unite behind their declaration.

Jefferson first turned to the two men he most trusted.

“Before I reported it to the committee, I communicated it separately to Dr. Franklin and Mr. Adams, requesting their corrections, because they were the two members of whose judgments and amendments I wished most to have the benefit,” Jefferson reflected.

John Adams was impressed.

“I was delighted with its high tone and the flights of oratory with which it abounded, especially that concerning [abolishing] negro slavery, which, though I knew his southern brethren would never suffer to pass in Congress, I certainly never would oppose.”

Adams referred to a passage in which Jefferson called for abolishing slavery. He blamed the crown for imposing the institution on the colonies. The passage was not included in the final declaration.

Congress was in such a hurry to see the committee’s work that Jefferson presented the document in his handwriting, not in typeset or printed form, on June 28, 1776.

Jefferson knew the task of convincing Congress to vote for the declaration was formidable because it was the boldest most courageous step the Continental Congress could possibly take. If any decision led to General Howe’s gallows, it was this one. Hence, Jefferson knew the document needed Congress’ wholehearted approval for its success. Unity would take a little time.

The delegates decided to first review Richard Henry Lee’s resolution for independence. Then they debated whether to adopt Jefferson’s declaration.

The debate centered on two major points of conflict: criticism of the common people in England and slavery. Even though the British nobility was corrupt along with the king, several members wanted to distinguish the British government from the English people.

“For this reason, those passages which conveyed censures on the people of England were struck out, lest they should give them offence,” Jefferson wrote. “The clause too, reprobating the enslaving the inhabitants of Africa, was struck out in complaisance to South Carolina and Georgia.”

Withstanding the criticism for his writing from members of the Continental Congress was difficult.

Throughout the debate, Jefferson tried to be “a passive auditor of the opinions of others, more impartial judges than I could be, of its merits or demerits.”

Elder statesman Benjamin Franklin sat next to Jefferson during the discussions.

Franklin tried to cure Jefferson’s despondency with funny stories and “observed that I was writhing a little under the acrimonious criticisms on some of its parts,” remembered Thomas Jefferson.

The clock kept ticking. The debate would not abate for another three days. As often happens, achieving unity required both time and endurance.

Full-Grown Patriots

“The second day of July 1776, will be the most memorable epoch in the history of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated by succeeding generations as the great anniversary festival,” John Adams wrote to his wife Abigail on July 3, 1776.

Congress’s decision to adopt Richard Henry Lee’s resolution for independence on July 2, 1776, set off fireworks in Adams’s patriotic soul.

“It ought to be commemorated, as the day of deliverance, by solemn acts of devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with pomp and parade, with shows, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires and illuminations, from one end of this continent to the other, from this time forward forever more,” proclaimed Adams.

But July 4, the day Congress adopted Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence, not Lee’s resolution, became the holiday known as Independence Day.

Both the resolution and the Declaration were important for another reason. Members of the Continental Congress had transition from Sons of Liberty into full-grown patriots who knew what they believed and were ready to die for it.

“This, however, I will say for Mr. Adams, that he supported the Declaration with zeal and ability, fighting fearlessly for every word of it,” Thomas Jefferson later wrote.

Jefferson graciously honored Adams for advocating the rights of the Revolution.

“For no man’s confident and fervid addresses, more than Mr. Adams’, encouraged and supported us through the difficulties surrounding us, which, like the ceaseless action of gravity, weighed on us by night and by day.”

With great discipline and respect, Congress had debated the Declaration of Independence for three days. On July 4, every member who was present, except for one, voted for the Declaration. John Dickinson of Delaware was the exception.

“The sentiments of men are known not only by what they receive, but what they reject also,” Jefferson wrote about Dickinson.

Dickinson had not come to terms with the fact that the king had rejected the olive branch petition he had drafted a year earlier. The seed of independence had fallen on rocky soil in Dickinson, the man known as the farmer.

The seeds of patriotism had fallen on the most fertile soil in John Hancock’s soul. He is the primary reason why history remembers July 4 more fondly than July 2. As president of the Congress, Hancock bravely and boldly signed the Declaration on July 4. The remaining members signed it on Aug. 2. Each signature showed courage. Each “John Hancock” provided tangible proof of treason in the eyes of the British.

Another reason July 4 became known as Independence Day is because Congress distributed the Declaration of independence, not the resolution, on broadsides and in newspapers throughout each the new 13 states on broadsides. They sent copies to assemblies, public safety committees, and the Continental Army.

Congress hoped their declaration would light a fire among the people. And indeed it did. The Declaration of Independence turned a rebellion into a revolution.

The Unanimous Declaration

The Declaration of Independence gave the United States of America a Genesis-like foundation. Though its bullet-point complaints pinpointed King George III as a tyrant, its themes were universal and transcended continents and generations. Why did the Declaration seize the hearts of the people?

First, the Declaration was unanimous. Although John Dickinson voted against it, he was overruled by his fellow delegates from Delaware. Hence, the declaration derived its power from its one-state, one-vote unanimity. This single voice of separation from England soared throughout America’s skies, seas, and soil.

“THE UNANIMOUS DECLARATION OF THE THIRTEEN UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,” the document began.

Second, the Declaration was respectful of those most affected by the separation.

“WHEN in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another . . . a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation,” the Declaration stated before outlining the details of their grievances.

Third, the Declaration was rooted in the belief that God valued life and liberty.

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

Fourth, the Declaration was secure against an avalanche of abuse by authority. It called for claiming those God-given rights through an accountable government. Humanity had a right to disband government if that government abolished those rights.

“That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government,” the document asserted.

Fifth, the Declaration was sensible. Although its ideas were radical, its demands were not impractical. What kept the Declaration from justifying the continuous overthrow of governments was this statement:

“Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes.”

Sixth, the Declaration was justifiable.

After presenting these universal ideas, the Declaration presented 27 bullet points or facts, to candidly prove the king’s “absolute Tyranny over these States.”

Seventh, the Declaration looked to a higher authority.

It appealed “to the Supreme Judge of the world” and declared, “That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States; that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved.”

Through these universal themes, the Declaration championed human life. The founders sought to restore order out of chaos by seeking to protect the rights of those created in the image of God. They traded royalty for representation.

PRAYER

Thank you for declaring your love for me, for creating me in your image, for endowing me with life and liberty. Thank you for the brave souls who lived loudly for liberty in 1776.

To learn more, check out Stories of Faith and Courage from the Revolutionary War by Jane Hampton Cook.