George Washington and the Army’s First Thanksgiving

Did the United States of America become a great nation because Americans were grateful along the way? So it seems.

Despite their grievances with King George III after he harshly taxed them, abolished their legislatures, paid their judges’ salaries and implemented martial law, the colonists created a culture of gratitude. Leading the way was General George Washington, who discovered the New England tradition of Thanksgiving 250 years ago this month.

Washington wrote the word Thanksgiving for the first time on Nov. 18, 1775, when he commanded the Continental Army. Though Washington had long valued giving thanks to God and to others as part of his good manners, he discovered that the leaders of Massachusetts set aside a day for Thanksgiving each autumn after the harvest. He ordered his army to celebrate Thanksgiving along with the people in Massachusetts.

One of his first acts as commanding general was to show gratitude. When the Continental Congress commissioned him as commanding general in June 1775, he thanked them for the trust they had placed in him.

“Mr. President (John Hancock), tho’ I am truly sensible of the high honor done me in this appointment, yet I feel great distress, from a consciousness that my abilities and military experience may not be equal to the extensive and important trust,” Washington wrote to the president of the Continental Congress.

“However, as the Congress desire i⟨t⟩ I will enter upon the momentous duty, and exert every power I possess in their service and for the support of the glorious cause: I beg they will accept my most cordial thanks for this distinguished testimony of their approbation.”

Washington took charge of the piecemeal army in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in July 1775 after months of chaos. The year had been devastatingly bleak, with seemingly little to be grateful for. The first shots of America’s Revolutionary War had taken place on April 19, 1775, when British soldiers had marched into the Massachusetts countryside. Their mission had been to capture the Sons of Liberty’s leaders, John Hancock and Samuel Adams, in Lexington and to confiscate the patriots’ ammunition, guns and gunpowder in Concord.

Though the British redcoats had failed to do either, the result nonetheless had been war. The first shots of America’s Revolutionary War had been fired in Lexington and Concord. Two months later on June 17, 1775, more fighting had taken place near Boston at Charlestown in the Battle of Bunker Hill.

When Washington arrived to take charge of the army in Cambridge, he had faced a stalemate. The British had full control of Boston proper while the colonists surrounded them in the countryside through their militias. Washington’s task was to unite his army and drive the British from Boston as soon as spring sprung in 1776.

As he waited for the seasons to pass, Washington discovered the new custom. The people in Massachusetts set aside a day of Thanksgiving each fall. General Washington asked his soldiers to join in this tradition, which made November 23, 1775, the army’s and Washington’s first Thanksgiving day.

Tough the words thank, gratitude and grateful appear numerous times in his writings, this was the first time that Washington wrote the word thanksgiving in his correspondence. He told his army that “The Honorable Legislature of this Colony” had “set apart Thursday the 23rd of November instant, as a day of public thanksgiving ‘to offer up our praises, and prayers, to Almighty God, the source and benevolent bestower of all good.” He looked to God to “smile upon our endeavors, to restore peace, preserve our rights … and avert the calamities of a civil war.”

Thanksgiving is older than the United States of America. There are five first Thanksgivings. More than 50 Mayflower pilgrims and nearly twice as many members of the Wampanoag had held a joint three-day thanksgiving feast in 1621. Though they had many cultural differences, both groups had shared the value of giving thanks to God their creator.

Virginians had also prayed and given thanks to God in 1607 and 1619 but it did not become an annual recurrence because of the 1622 massacre. Both French Protestants and Spanish Catholics had held one-time thanksgivings in Florida in the 1560s, while the Spanish explorer Coronado had held a Thanksgiving service and feast in Palo Duro Canyon, Texas, where they had celebrated with the help of the Tejas tribe, who had hunted buffalo. The first European thanksgiving appears to have been a barbecue, not a turkey roast. Imagine that.

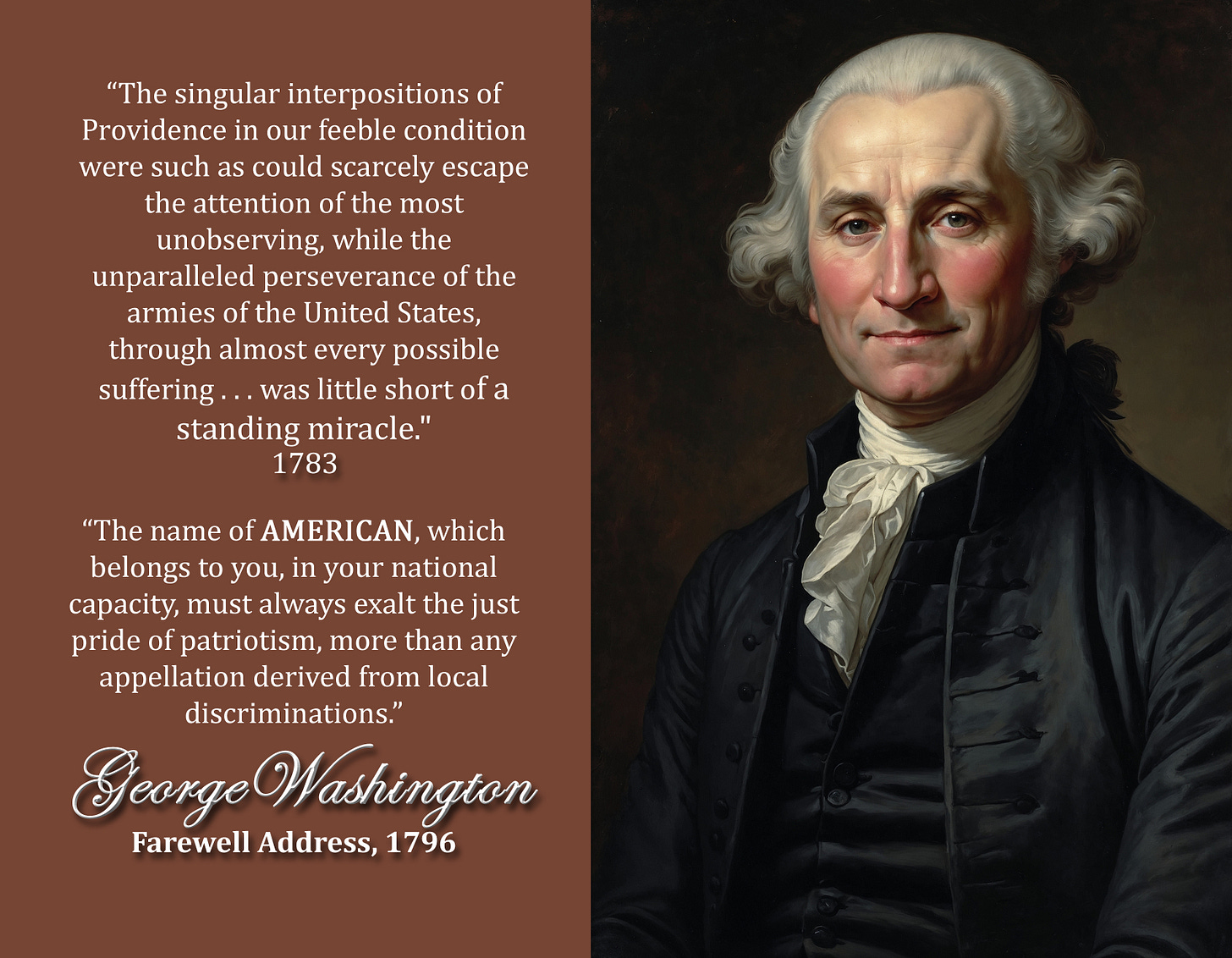

Throughout the American Revolution, the Continental Congress and George Washington set aside days for giving thanks to God, whether the occasion was to celebrate their alliance with France in 1778 or to pray and give thanks while they were in distress as they built their camp at Valley Forge. They nurtured an attitude of gratitude along the way.

We can learn from the first generation of Americans this Thanksgiving. Instead of saturating our minds with our grievance culture, let us celebrate the blessings in our lives and country. No one alive today should look with despair at their future because of the sins in America’s past. Instead, may we celebrate and show gratitude for the good and great in our past with truth leading the way, especially as we celebrate the upcoming 250th birthday of our nation on July 4, 2026. Thanksgiving reminds us that gratitude is central to celebrating.

Revolutionary Readers for America’s 250th

From America the Beautiful in the series Revolutionary Readers for America’s 250th.